People think of pickle relish and chutney as cousins at the condiment table. They’re both punchy, chunky, a little tangy, and sometimes weirdly sweet. But would any grandmother from Gujarat ever call hot dog relish a chutney? Or, put another way—can you really smear Great Auntie’s mango chutney on a hot dog? Weird, right? You’re not the first to pause with a jar in hand, wondering if pickle relish is secretly just a chutney with a different passport. This whole thing gets a lot more complicated (and fun) when you look deeper than just the cute jars in your fridge.

The Roots: Where Pickle Relish and Chutney Really Come From

Most American kitchens recognize pickle relish as a hamburger or hot dog essential. The classic neon-green stuff likely showed up with the vaudeville era, right about when street vendors realized you could make vinegar, cucumbers, and sugar dance together and people would pay extra for it. Some sources point to relish as a descendant of early American "piccalilli," a term imported from Britain, which meant any oddball chopped pickle seasoned with tang and spice.

Chutney? Now there’s a word with ancient roots. It comes from Hindi "chatni," literally meaning "to lick"—so, something tasty, not always liquid, but always worth licking off your fingers. Chutney can mean a whole universe of spreads in India. There’s coconut chutney beside dosa, coriander chutney in Mumbai sandwiches, and then looming large: the sweet, tangy mango type, packed with spice. People started calling any cooked, preserved fruit or veggie mixture with vinegar and spices “chutney” once the British carried the idea back from India in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Oxford Companion to Food notes,

“Chutneys evolved in parallel with pickles, but became their own tradition in Indian and Anglo-Indian cookery.”Most grandmothers in India wouldn’t recognize a jar of hot dog relish as anything remotely related—but the British-Chutney hybrids on supermarket shelves muddy the lines.

This is really a case of cultural overlap. Both chutneys and relishes pop up around the world, wherever people figured out that sweet, sour, spicy, and crunchy belong on the same plate. But the label speaks to heritage. Relish turned into a subcategory of pickle in the U.S., while chutney took on a more exotic, sometimes misunderstood, identity in the West.

What Actually Goes In: Exploring Ingredients and Preparation Methods

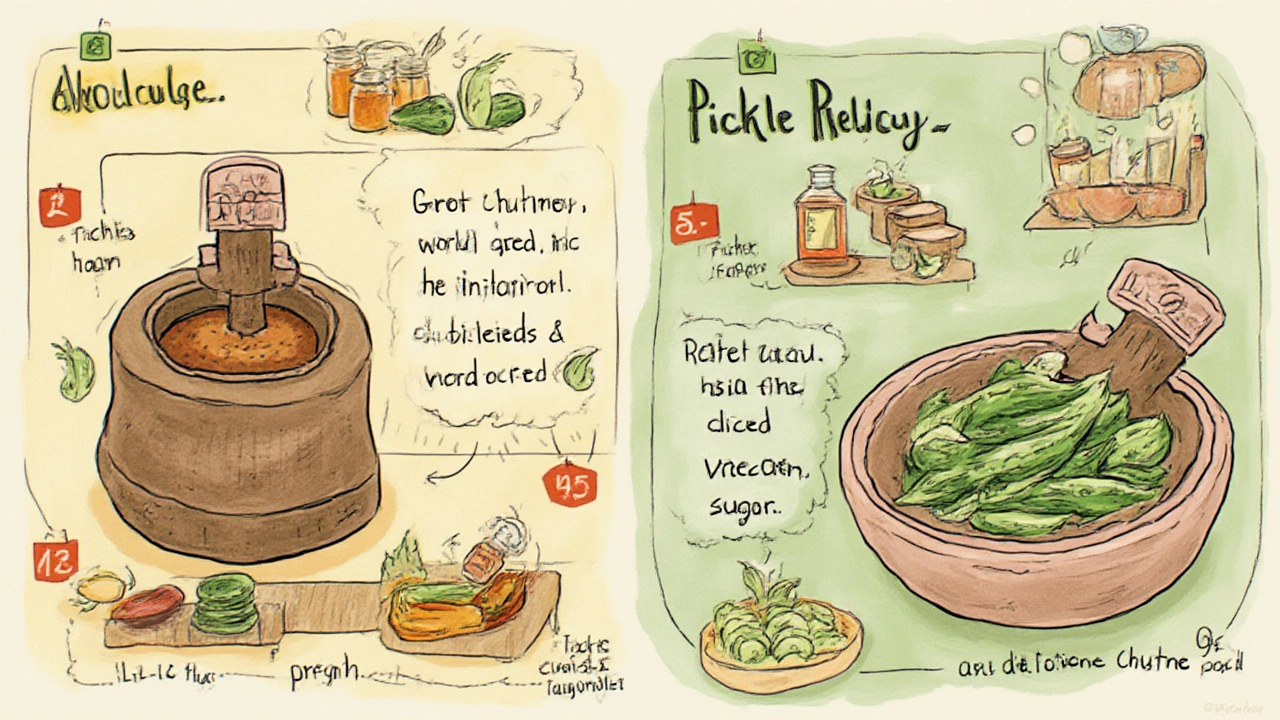

This is where it gets interesting. If you look at two random jars—one labeled "pickle relish," the other "chutney"—they might look kind of similar. But details tell another story.

Pickle relish, especially the typical American kind, almost always starts with finely chopped cucumbers (sometimes mixed with peppers or onions). The main flavor stages are vinegar for tartness, a real hit of sugar for that sweet note, and maybe a suspiciously glowing green food dye. Spices? Sometimes celery seed. Occasionally mustard seed. Most of the magic comes from sugar and vinegar.

Chutney, by contrast, is all about variety. In Indian kitchens, you can find raw chutneys (think coriander, mint, coconut blitzed with lemon), and cooked chutneys (mango, tamarind, even tomato, stewed down with warming spices). The British-style mango chutney you see at the shop likely contains fruit, vinegar, sugar, ginger, chili, mustard seed, maybe fenugreek. No two recipes are ever exactly alike.

Preparation methods matter. Relish is almost always pickled. There’s a brine stage—chopped veggies sit in salt or vinegar to draw out water, then they go into a vinegar-sugar bath and get bottled up. Some store-bought types are barely cooked at all, more preserved than transformed. Chutney’s story depends on the style. Many cooked fruit chutneys are simmered for hours, almost like a savory jam, until they thicken up and take on layer after layer of spicy, sweet, and tangy flavor. Fresh chutneys can be raw and vibrant—pounded, ground, or blended—but always intense.

The seasoning is the clincher. Western pickle relish relies on celery seed, dill, or mustard, but rarely the bold spices you’ll find in Indian chutney. Chutney likes to strut its stuff: cloves, cinnamon, cardamom, cumin, even curry leaves sometimes join the party. You won’t usually find these in American relish. Because chutneys adapt to what’s fresh and local, you might throw in green mango, pineapple, or even peanuts. Relish rarely strays from its cucumber roots.

If you side-by-side compared a Brit’s Branston pickle (which is more of a chunky relish) and an Indian’s date-tamarind chutney, you’d taste the difference in seconds. Still, sometimes the labels cross over. You’ll see “chutney” written on sweet-hot pepper relish made in Pennsylvania, and “relish” tagged onto old Anglo-Indian-style chutneys in UK grocery chains—confusing, but that’s marketing not tradition.

Here’s a quick breakdown:

| Aspect | Pickle Relish | Chutney |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | USA/UK | India |

| Main Ingredients | Cucumbers, vinegar, sugar, onions | Fruits/veggies, spices, vinegar, sugar |

| Cooking | Usually minimal | Often simmered (for cooked chutney) |

| Flavors | Tangy, sweet, sometimes spicy | Sweet, tangy, spicy, aromatic |

| Common Spices | Celery seed, mustard, dill | Cumin, coriander, ginger, chili, more |

| Color | Bright green or yellow | Usually darker or earthy |

If you’re looking for a shortcut: Relish is usually cucumbers plus sweet. Chutney is fruit, veg, intense spice, and no rules.

How They’re Used: Cultural Roles and Kitchen Swaps

This is where the debate heats up. Imagine trying to swap the classic pickle relish in your Chicago dog for a spoonful of spicy mango chutney. It might sound cool, but the flavors would clash like mismatched shoes. Relish is made for the American palate—it cuts through rich meat, adding tang without too much heat. You spoon it on burgers, dogs, smoked sausages, and even use it in potato salads and egg salad for a little zip.

Chutney’s story is more versatile—and older. In Indian food, chutneys sit beside curries, grilled meats, fritters (pakoras), rice, dosa, and idli. There’s almost always a fresh or cooked chutney on the table at big family feasts. You don’t just use one kind: two or three are the norm. Each has a job. Coriander-mint cools your palate, coconut chutney balances heat, tamarind adds zip. There’s a spread for every mood and dish.

Modern food trends in the U.S. have thrown these boundaries up for grabs. Suddenly, restaurants are dolloping fruit chutney over roast chicken, mixing onion chutney into grilled cheese, or streaking spicy tomato relish across a seared steak. Fusion is the new normal. But straight up, using hot dog relish in place of a chutney on a dosa would baffle an Indian grandma. It’s technically possible, but you’d definitely get a look.

What’s interesting is how both condiments punch above their weight. Want to add a twist to a turkey sandwich? Slather on a spoonful of tamarind chutney instead of relish, and you get a wallop of flavor nobody expects. Or, stir a thick onion relish (sometimes sold as chutney in the UK) into cheddar cheese for an ultra-British snack. The boundaries are fuzzy, but that just gives you creative license in the kitchen.

If you’re adventurous, consider making your own. Fresh Indian-style chutneys are wildly easy: just blend coriander, mint, ginger, green chili, lime juice, and a pinch of salt. For a British-style relish or chutney, simmer chopped vegetables or fruit, vinegar, sugar, and your favorite spices until sticky—think apple-chili or rhubarb-ginger. Homemade versions are fresher and let you control sugar and spice levels. Plus, you can invent your own combos—peach relish with basil, tomato chutney with smoked paprika, even pineapple relish with habanero.

- Sweetness: If you want less sweet, reduce the sugar. Homemade means flexibility.

- Spice: Add serrano pepper or goji berries for a kick.

- Consistency: For a chunkier result, chop coarse; for a smooth paste, blend longer.

- Pairings: Try tomato chutney with grilled cheese or peach relish with roast pork.

- Storage: Chutney and relish both last weeks if refrigerated, but chutney freezes well too.

If you’re at the grocery and confused by labels—look for the ingredient list. The more diverse and spicy, the closer to traditional chutney. Lots of cucumbers, celery seed, and neon color? That’s a classic relish. When in doubt, remember: If you want to impress at your next BBQ, bring a jar of homemade chutney and watch people’s reactions. It’s a step up from store-bought relish, and—let’s be honest—way more fun.